Last Updated on September 15, 2020, 9:52 PM | Published: September 15, 2020

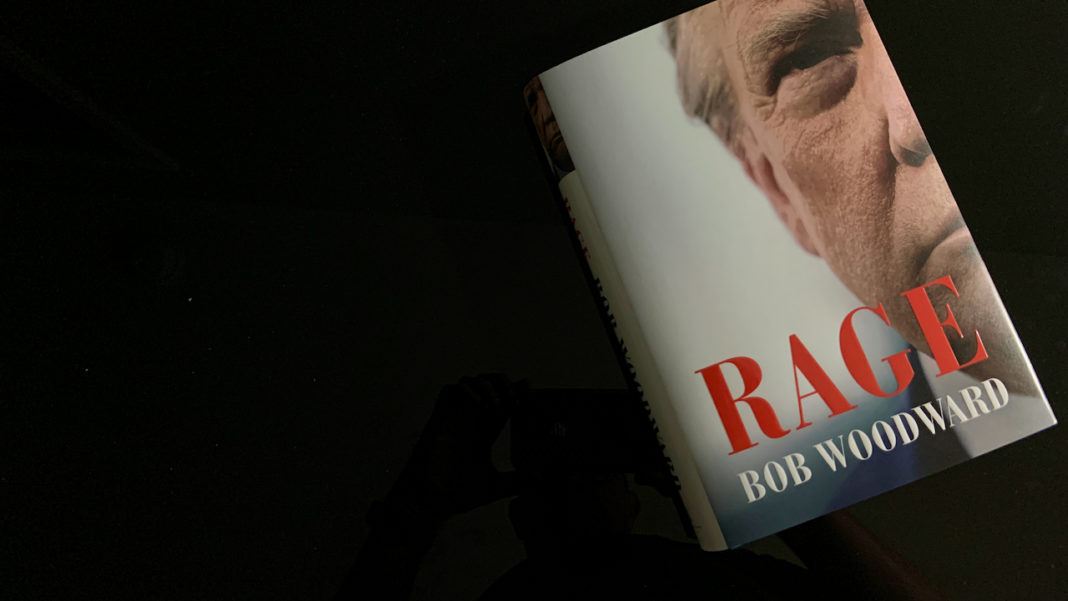

Bob Woodward’s Rage does not purport to be a scathing tell-all — those are being published almost weekly at this point in Donald Trump’s presidency. Instead, Woodward discovers through airtight research and copious interviews that Trump is not merely the wrong person for the job; he is openly hostile to doing anything correctly, culminating in his aggressive incompetence in dealing with the coronavirus epidemic.

For those who do not attend Trump superspreader events or post-Qanon fan-fiction on Facebook, the concept of a barely-there, easily distracted lump loitering behind the Resolute Desk is nothing new. But Rage confirms all suspicions and fears by presenting painstaking details of an administration that entered its tailspin on January 20, 2017 and never stopped plunging.

Opinion by George D. Lang

Many of those details come from the 18 interviews Woodward conducted with Trump, who unfailingly indicts himself as a ditzy megalomaniac who salivates over authoritarian rule but cannot maintain the focus to get through his daily intelligence briefing. But many others come from people who joined his administration to do what they saw as the right thing but learned of their inevitable firing or resignation on television or Twitter.

Key players include former Secretary of Defense James Mattis and former Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats, both of whom were considered “adults in the room” who could keep Trump in check. While Trump likes to dismiss such people as “disgruntled former employees,” in Rage they come off as accomplished old-school conservatives who found themselves playing nursemaids to a colicky, spiteful toddler.

“The President has no moral compass,” Mattis said.

“True,” Coats tells Woodward. “To him, a lie is not a lie. It’s just what he thinks. He does not know the difference between the truth and a lie.”

Mattis, the retired Marine general who got saddled with the Trumpian nickname “Mad Dog” when his actual infantry callsign was “Chaos,” describes in Rage the actual chaos of a daily intelligence briefing under Trump.

“It is very difficult to have a discussion with the president,” Mattis said. “If an intel briefer was going to start a discussion with the president, they were only a couple of sentences in and it could go off on what I kind of irreverently call those “Seattle freeway offramps to nowhere.”

Those offramps usually popped into view when Trump came to the daily briefing having freebased three hours of “Fox and Friends.” Woodward cites several instances in which Trump would be briefed on high-level confirmed intelligence and simply dismiss it by saying, “I don’t believe that” when it did not comport with what Steve Doocy, Ainsley Earhardt or Brian Kilmeade told him that morning.

Coats, a normally buttoned-up and mild-mannered former U.S. Senator from Indiana, is described in Rage as losing sleep and weight worrying about Trump’s coziness with despots like Vladimir Putin, Kim Jong-un of North Korea, and Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, rulers with the kind of power Trump craves.

But Rage is filled with the kind of feckless chumps that believe in the unitary executive theory, an idea that what the President says is true, legal and binding, no matter how malicious the intent, and is not answerable to any other branches of government.

U.S. Attorney General Bill Barr has pushed the unitary executive theory for years and is now putting it into practice for Trump. Former Deputy AG Rod Rosenstein is also a true believer who never missed an opportunity to undermine Special Counsel Robert Mueller or his findings on Russian election interference.

On this front, Mattis stands his ground on the branches of government, and he is reported in Rage as having repeatedly chastised lawmakers for rolling over for Trump.

“It is time for you to decide whether you are a coequal branch of government, or if you’re just going to talk like you’re one,” Mattis is quoted as saying to several members of Congress as he exited the administration. “I’m not here to tell you where to stand on an issue. But you seem to be awfully angry at times and you have the power of the purse. So what are you doing about it? I’ve done everything I can. When I was basically directed to do something that went beyond stupid to ‘felony stupid,’ strategically jeopardizing our place in the world and everything else, that’s when I quit.”

This is a stunning rebuke of congressional toadies like Senators Jim Inhofe and James Lankford, both of whom are derelict in their duties as members of the legislative branch. They allowed many of the events described in Rage to happen without acting as a check against Trump’s many abuses of power.

Rage continues through to the current pandemic when Trump informs Woodward in February of his advisers’ dire forecast. Five weeks later, as COVID-19 tightens its grip on the nation, Trump tells Woodward that he “wanted to always play it down. I still like playing it down. Because I don’t want to create a panic.”

Woodward caught heat following the release of audio recordings of those conversations, with critics arguing that Woodward should have alerted the public about Trump’s charade. They have a point, but sheer mountains of evidence in Woodward’s book point to the likely outcome: Trump would have called it “fake news” and half of the country would believe him. Just like they do now.

Will Rage change anything about the 2020 election? For reasons stated above, I doubt it. But Rage will solidify our future understanding of Trump’s disastrous reign, a time when the Watergate-era “cancer on the presidency” Woodward reported nearly five decades ago recurred and metastasized.

George Lang has worked as an award-winning professional journalist in Oklahoma City for over 25 years and is the professional opinion columnist for Free Press. His work has been published in a number of local publications covering a wide range of subjects including politics, media, entertainment and others. George lives in Oklahoma City with his wife and son.