Last Updated on August 6, 2023, 2:57 AM | Published: March 18, 2022

OKLAHOMA CITY (Free Press) — A school voucher bill that has divided the statehouse advanced in the Senate last week, and new estimates show the program would likely cost over $116 million.

Senate Pro Tem Greg Treat, R-Oklahoma City, authored the legislation, which would provide state dollars to students to spend on private school tuition and other education expenses instead of attending a public school.

The bill has a ways to go before becoming law, but it’s already one of the most talked about and debated pieces of legislation this year. It’s also a priority of Gov. Kevin Stitt, and has attracted out-of-state dollars into Oklahoma to push for its approval.

UPDATE, Friday, March 18: The state Senate was expected to take up the much-talked about school voucher bill this week. It didn’t happen, and lawmakers are taking a spring break through the rest of this week.

Here are some questions and answers about the proposal.

What’s the status of SB1647, and what are its chances of becoming law?

The bill cleared the Senate appropriations committee by a 12-8 vote last week; one Democrat voted for it, and five Republicans were against it. Previously, the bill narrowly won approval in the Senate education committee by an 8-7 vote. Treat and Senate Floor Leader Greg McCortney, R-Ada, are ex-officio members of all Senate committees, and it took their votes to pass.

Since it has committee approval, the bill is available to be heard on the Senate floor.

Its chances in the House, though, are slimmer. House Speaker Charles McCall said recently the bill won’t get a hearing in his chamber. McCall, R-Atoka, questioned the proposal’s benefit to students in rural communities.

“For a person that lives in Atoka, Oklahoma, population 3,000 people, 12,000 in the county, what does a kid with a voucher do?” McCall said. “The population is so sparse, are there going to be options that really pop up?”

The latest

McCall’s comments drew the attention of Club for Growth, a right-wing organization based in Washington, D.C. that has spent $71.2 million in 2020 on issues like reducing income tax, budget reform, tort reform, school choice and deregulation, according to factcheck.org.

Club for Growth Action, its super PAC, had raised $32 million as of Jan. 31 for the 2022 election cycle; nearly three-quarters of its money comes from three donors.

Club for Growth Action spent $25,000 to air television commercials on broadcast and Fox News in the Ada and Sherman, Texas, areas, pressuring McCall to hear the bill and accusing him of “silencing parents.” They also are sending mailers to his residents in his district.

How would the vouchers work?

Changes were made to the proposal last week as Treat attempted to address some main criticisms. First, an income cap was added (the original version left it open to any student in the state, regardless of family income.) In the current version, students would qualify if their family earns less than three times the amount to be eligible for reduced price lunches at school; for a family of four, that’s $154,000.

Another change: homeschoolers would not qualify for a voucher. That was amended after conservative homeschooling organizations opposed the bill.

Here are the main provisions, as written now:

• Vouchers would be worth an average of $5,942 to $8,116 — but as high as $17,500 — per student per year, depending on the student’s needs, according to the state Department of Education. The funds would be deposited monthly.

• There is no requirement that students previously attended public school.

• Funds could be spent on private school tuition and fees; tutoring; classes and extracurricular activities at a public school; textbooks, curriculum and other materials; computers; school uniforms; testing fees and prep classes; concurrent enrollment at a technology center or college; educational services and therapies; transportation; and other approved expenses.

• Unused money would roll over year to year.

• Participants couldn’t also receive a Lindsey Nicole Henry Scholarship, which provides a state-funded voucher to parents of children with disabilities to pay for tuition at a private school.

• The program would be managed by the Office of the State Treasurer.

Is this a school voucher proposal or an “Education Savings Account”?

Treat and other supporters draw a distinction between his plan and school vouchers. They say it’s technically an education savings account because the funds can be spent on more than just private school tuition. The term he uses in the bill is “Oklahoma Empowerment Account.”

Nationally, education savings account legislation has become more favorable because of the ability to bypass Blaine Amendments, which are constitutional provisions in some states – including Oklahoma – that prohibit state money from going to religious organizations, like many private schools.

A voucher is defined as “a coupon issued by government to a parent or guardian to be used to fund a child’s education in either a public or private school,” according to Merriam-Webster, and that describes Treat’s proposal.

Public data on students who receive a private school voucher through a decade-old program is almost non-existent. State law requires demographic information to be reported annually.

How much would it cost?

The total cost depends on how many students enroll, and that’s difficult to project. The state Education Department estimates that 19,945 students would participate – that’s 2.63% of all public, private and homeschool students combined, which was the participation rate in Florida’s Family Empowerment Scholarship Program in 2021-22.

That projection creates a total annual cost of between $119 million and $162 million.

Treat, in the appropriations committee meeting Wednesday, gave his word that the plan would not have a negative impact on public school funding.

“I want you to hear me loud and clear: we will not pursue final passage on this bill if we cannot find the money to offset the cost in the state aid formula, not just for this fiscal year but on an ongoing basis,” he told the committee.

Treat hasn’t provided specifics on how the Legislature would find the funding.

Who are the supporters? Why do they support it?

The Oklahoma Council of Public Affairs, a right-leaning think tank, has been one of the most vocal supporters. More than a dozen articles on their website mention the bill.

The organization is behind a Twitter campaign in which automated tweets tagged McCall and demanded the bill be heard in the House. Known as astroturfing, this type of campaign attempts to create a false impression that there’s a spontaneous grassroots movement around public policy issues.

The organization supports the bill because it holds that low-income students should be able to pay for private school tuition like wealthy families, and that public schools would improve when faced with competition for public dollars.

Other supporters include Gov. Stitt, who has championed the idea to “fund students, not systems” on a Fox business TV segment and at the Conservative Political Action Conference last month.

Former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, whose family founded the national school privatization lobbying group American Federation for Children, thanked Stitt for support of school choice on Twitter Feb. 28.

Jeb Bush, former Florida governor and founder and chairman of ExcelinEd, a national education policy reform group, applauded the proposal in a statement on the organization’s website. Last year, Stitt brought Bush to Oklahoma to speak to legislators about education reform policies.

Who’s against it? What are their concerns?

Opposition from conservative homeschooling organizations led Treat to amend the bill last week so that homeschool students wouldn’t qualify. One group, Reclaim Oklahoma Parent Empowerment, opposes voucher programs because they say it leads to government overreach (They do, however, support tax credit programs that fund private school tuition scholarships.)

Public school superintendents have stated opposition to the proposal. Sand Springs Superintendent Sherry Durkee told the Tulsa World the “my tax dollars, my money” idea is flawed because taxes are intended to be pooled together to provide shared public services, including education, public safety and infrastructure.

Educators in rural communities are particularly concerned. Don Ford, executive director of the Organization of Rural Oklahoma Schools, said the impact on small-town schools could be devastating. “The plan offers no benefit to students and families in our rural communities, yet we will still pay the price – literally – if this bill becomes law,” he wrote in a column in the Tulsa World.

Joy Hofmeister, state superintendent of public instruction, who is running for governor, called the bill a “rural schools killer.” The Oklahoma State School Boards Association, an organization representing elected school board members, opposes voucher legislation and is urging lawmakers to work on “real solutions” for the nearly 700,000 students attending public schools.

Several lawmakers, as well as the group Pastors for Oklahoma Kids, have decried the measure as unconstitutional. Article 13 of Oklahoma’s constitution requires the Legislature to “establish and maintain a system of free public schools wherein all the children of the state may be educated.”

Will the proposal help low income students attend private school, as its proponents claim?

Private school tuition varies greatly depending on the school. At one Oklahoma City church-based school, where tuition is less than $3,000 per year for church members, a voucher would likely fully cover the cost. But at another school, where kindergarten tuition exceeds $15,000 for kindergarten, a voucher would amount to a coupon.

Private schools enroll far fewer low income students than public schools. At 55 state private schools that reported the percent of low-income students enrolled, only half said at least a quarter of their student population was low income. That’s the average in Edmond Public Schools. At nine of the schools, fewer 10% were. The average among Oklahoma public schools is nearly 60%.

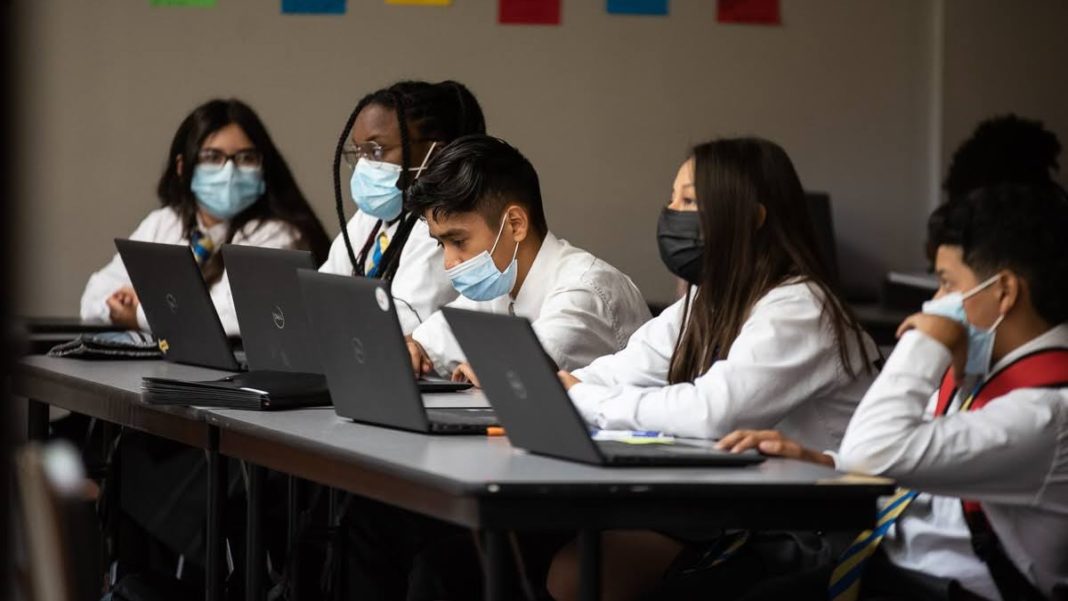

There are a few private schools that focus on serving low-income communities, like Cristo Rey Catholic High School in Oklahoma City, which has 260 students this year. Cristo Rey’s tuition is about $15,000 per student, but families pay an average of $1,000, and up to $2,500. The difference is covered by private donations and a corporate work study program.

But having families pay a small amount of tuition is part of their model and amounts to having “skin in the game,” said Cristo Rey President Chip Carter. If Treat’s proposal becomes law, the vouchers would likely be used to offset Cristo Rey’s costs, not families’.

Do other states have similar programs?

Eight states have “education savings account” type programs: Arizona, Florida, Indiana, Mississippi, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Tennessee and West Virginia, according to EdChoice, an Indiana-based organization that promotes voucher, charter school, and tax credit scholarship policies.

Additionally, 16 states plus Washington, D.C. and Puerto Rico have voucher programs, including Oklahoma, which has the Lindsey Nicole Henry Scholarship program. Treat’s voucher proposal would not allow students to receive both.

Several studies of voucher programs in Indiana, Louisiana, Ohio and D.C. found no effect or a decline in student achievement. But other research has shown voucher programs had a positive impact on attending college or graduating from high school.

School quality can be an issue, and one that is barely regulated by states with voucher programs. An Orlando Sentinel investigation of private schools in Florida’s scholarship programs — the longest running in the country — found teachers without certification or even bachelor’s degrees, substandard curriculum and unsafe buildings, among other issues.

Treat’s proposal would not impose any additional standards on the participating schools or service providers, and explicitly gives them “maximum freedom” to address the education needs of students. Proponents say it’s parents who provide the ultimate accountability.

But in Florida, parents complained repeatedly to the state Education Department, which responded it had no control over the way the private schools conducted their business.

First published in Oklahoma Watch on March 11, 2022, and published here under Creative Commons license. Free Press publishes this report as a collaborative effort to provide the best coverage of state issues that affect our readers.

Feature photo caption: Students are seen working on their computers in Ms. Kenney’s bible class at Cristo Rey, a private Catholic high school in Oklahoma City in this August 19, 2021 file photo. (Whitney Bryen/Oklahoma Watch)

Jennifer Palmer has been a reporter with Oklahoma Watch since 2016 and covers education. Contact her at (405) 761-0093 or [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @jpalmerOKC