Last Updated on May 24, 2021, 4:27 PM | Published: May 22, 2021

This week, survivors of the Tulsa Race Massacre testified before Congress, bringing renewed attention to the long and fraught history of African Americans in Oklahoma. For many, the attention is long overdue, with many of the survivors aging into their hundreds.

For others, the attention is unwanted, especially after the Governor of Oklahoma signed into law a ban on blunt teaching about our fraught past of racial brutality and disharmony including “critical race theory” in schools.

But for Oklahoma City, the attention is perfectly timed to provide its residents with the opportunity to reflect on its own past and its future as the city rapidly evolves.

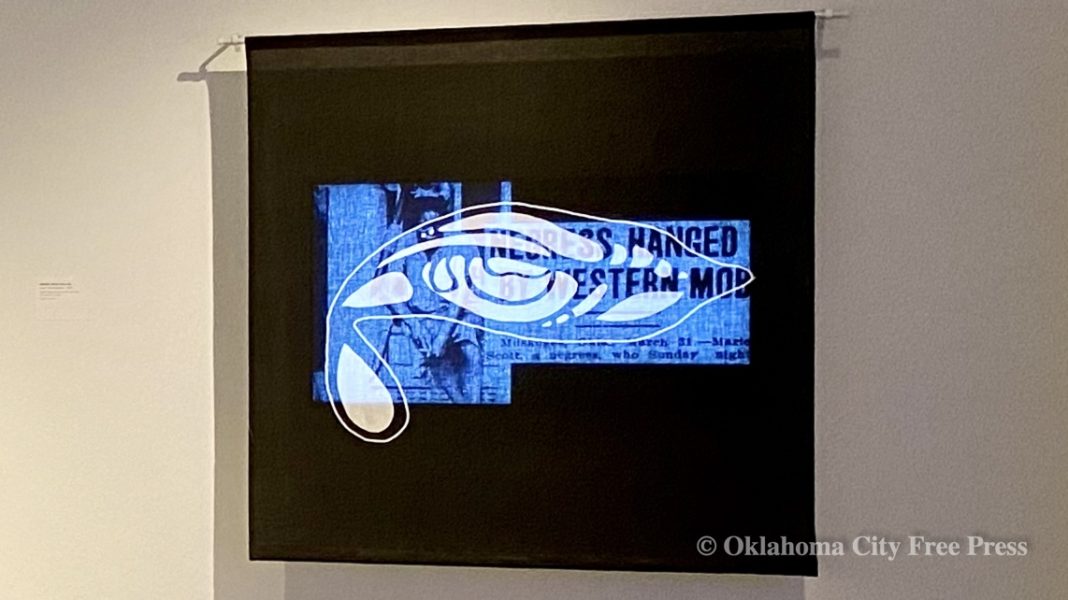

Oklahoma Contemporary’s much-anticipated new exhibit, “We Believed in the Sun,” distills the lessons of history in highly individualized stories by two Oklahoman artists, providing an approach that’s attached to the lived Black experience of America.

The Arts

with Devraat Awasthi

Clara Luper speaks on the walls of Oklahoma Contemporary, greeting visitors with the title of the exhibition: “I came from a family of believers. We believed in the sun when it didn’t shine. We believed in the rain when it wasn’t raining. My parents taught me to believe in a God I couldn’t see.” For visitors, this is much-needed sustenance from an esteemed ancestor, and centers hope in the narrative that Ebony Iman Dallas and Ron Tarver begin to unravel.

The two artists exhibited in the gallery hadn’t actually met before the exhibition launched this month.

Ron Tarver is a prominent Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer and 2021 Guggenheim Fellow, born in Fort Gibson and based in Philadelphia. Ebony Iman Dallas is a fresher face, younger and closer to home. Tarver’s photographs are black-and-white, leached of their color, and Dallas’ carvings and paintings are filled with vibrant pigments. Both share a background in journalism.

Together, their art creates a dynamic posture that juxtaposes two different but surprisingly compatible approaches to storytelling. Their works put each other in relief, alternately contrasting and focusing.

Tarver gave credit to the curation and remarked on the surprise he felt when he first saw the exhibition; having never met Dallas, he hadn’t been sure what the effect would be, but was delighted by the result.

Tarver’s photographs reflect his past as a photojournalist, first breaking barriers at the Muskogee Phoenix before his list of achievements grew. But the urge “to tell stories, to introduce readers to people they’d never met” that first prompted his start in journalism remains the underlying theme of his work.

At their base, his photographs are documentary. Their lens is surgically precise in subject and depth, conveying an interested but mournful glance at the lost chapter of history that is Deep Deuce.

His choice of black and white for his photographs artfully historicizes the photographs despite being taken relatively recently. The effect of black and white photography on viewers to perceive the image almost immediately through a historical perspective is particularly useful in “We Believed in the Sun.”

But the reason Tarver photographs in black and white is not to trick viewers into intellectualism. It is, rather, to distill the “essentials of the image.” He theorizes that color is information, and when color is filtered out, so is extraneous data, forcing the viewer to focus.

Tarver’s approach squares directly against the approach of Ebony Iman Dallas. Dallas’s background as a graphic designer is immediately apparent in the bold and uninhibited leap into color she takes in her pieces. Her approach is shaped by her background as a “fifth-generation Oklahoman and second-generation Somali-American,” a proud reminder of her heritage. A painting by Dallas that immediately draws visitors’ attention, “London, Hargeisa, Cairo,” challenges conventional ideas of love, time, and their intersection. It is one of her finest works on display, and demonstrates the generational arch of her gaze.

The carefully drawn borders and textured imagery of her work evinces a perfectionism honed and battled with.

Recalling her visit to Somaliland, Somalia, Dallas spoke about her frustration with attempts to capture a photograph in painting and turning to henna designs to exercise repose and ask herself if she “has something valuable to contribute besides replicating photographs.”

That work paid off and remains a tenet of her method. Her orientation to justice and social issues was shaped early in life and is meaningfully displayed in her work by the vibrant use of gold leaf to “honor subjects who are not treated as full human beings by our media.”

The contrast built by Tarver and Dallas’s art is startlingly satisfying.

Tarver emphasizes a more precise, scientific methodology, and this is preserved by the neat square and rectangle frames that separate Tarver and Dallas. But Dallas’s color bleeds through the frames, artfully carved and sculpted, to tell a joint story about lost fathers and a city’s past. For Dallas, these points of connection are key. They provide visitors with a story of continual healing, shared not only by the artists on display, but also with the city they are displayed in, and the visitors they are displayed to.

From the beginning of the exhibition to the end, Clara Luper’s voice travels with visitors. Her own story is often forgotten, along with the stories of Black Wall Street and Deep Deuce. In return for her unmatched service to the city and to Oklahoma, her legacy as one of the founding mothers of the Civil Rights Movement is sidelined.

Her name was bestowed on 23rd Street to honor her memory, and today, as the city government channels millions to tourism-oriented infrastructure, the long and languishing Clara Luper Corridor lies neglected.

The reflection of Tarver and Dallas is an optimistic one, and one grounded in neglected stories revitalizing. The skill with which Tarver and Dallas make old lives new is one that is punctual at a time where all Oklahomans endeavor to repair and rejuvenate, in more ways than one.

The exhibition runs through August 9. Tickets are free.

Devraat Awasthi is an art reporter for Free Press, a full-time law student at the University of Oklahoma, and is interested in pop culture’s role in public communities.