Last Updated on February 16, 2021, 2:57 PM | Published: February 14, 2021

The Supreme Court’s decision last year in McGirt v. Oklahoma forced a reckoning within the state, exposing bare the foundational yet fraught relationship between Oklahoma and the Native American tribes.

It also, however, gave the force of law to a principle long held sacred by the tribes of Oklahoma: that custody of their land, as it has for centuries untold, remains unsevered from the First Nations.

That principle, expressed through years of exile, exploitation, and theft, is given voice in the meticulously compiled exhibition, Spiro and the Art of the Mississippian World, launched Friday by the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.

Spiro Mounds traces the history of Oklahoma all the way back to its original inhabitants, the Mississippian Culture, and compiles an impressive array of artifacts that challenge deeply held notions about pre-Colombian America.

For children, too

For parents, Spiro Mounds is an ideal break from online learning.

The museum labels are simply written and take readers on a step-by-step analysis of the science, archaeology, and history of indigenous Oklahomans. In being so easy to understand, the Museum makes it easily accessible for children, which is of course part of the goal.

In “gearing the language towards children,” says Dr. Singleton, it “allows them to take an active role in the exhibition and better understand this country’s history.”

Education is the primary goal here, in part because we have done such a bad job of it before, and Dr. Singleton hopes “that people will see how incredible and unique the indigenous cultures of North America were before Europeans set foot in North America” as they go through the exhibition.

Treasured legacies

Spiro Mounds is a project ten years in making by Dr. Eric Singleton, the curator of the exhibition. Dr. Singleton’s study of the Spiro Mounds in Eastern Oklahoma is an effort to bring to public attention an era of Oklahoma history that often goes untaught or unnoticed.

But for the Wichita and Caddo tribal nations, the Spiro Mounds are treasured legacies of their ancestors.

The legacy of excavation of the Spiro Mounds is troubled by stories of looting and demolition, and, according to Dr. Singleton, “once looted and excavated, [material from Spiro] spread across the nation and world. The process of locating these items and identifying which pieces were relevant took many years.”

These years of careful, precise collection have delivered a staggering array of artifacts that challenge preconceived notions of pre-Colombian Oklahoma. That struggle is felt not only by viewers but also by the curators and archaeologists who make these discoveries.

Criticism

Today, museums face growing criticism for methods used in obtaining artifacts and the manner in which they are displayed. Often, artifacts are obtained through theft, looting, or one-sided bargaining.

Once obtained, artifacts are frequently showcased in a zoological manner as if the people these pieces represent are either non-human or simply no longer present. But the Museum and Dr. Singleton are highly conscious of these challenges and sought from the beginning to center the tribal nations in telling what is, according to Mr. Seth Spillman, the Museum’s Chief Marketing Officer, “an American story, no matter what you claim as your heritage – this is our collective heritage.”

From many collections

Many of the pieces collected and displayed in the exhibition are in fact on loan from different institutions in an effort to provide a more comprehensive and equitable storytelling. This reflects, as Mr. Spellman noted humorously, a kind of “irony,” as many of the artifacts from Spiro were actually brought there by peoples from across the American Southeast and beyond.

In many ways, the process of exhibiting these artifacts mirrors what must have been a significant and difficult compilation of items centuries ago. Displaying these artifacts in a manner “sensitive to their significance,” says Mr. Spellman, “is of the utmost importance.”

”These were people!”

In shaping this exhibition, Dr. Singleton began his work in the tribes of the Spiroan descendants themselves, the Wichita and Caddo Nations.

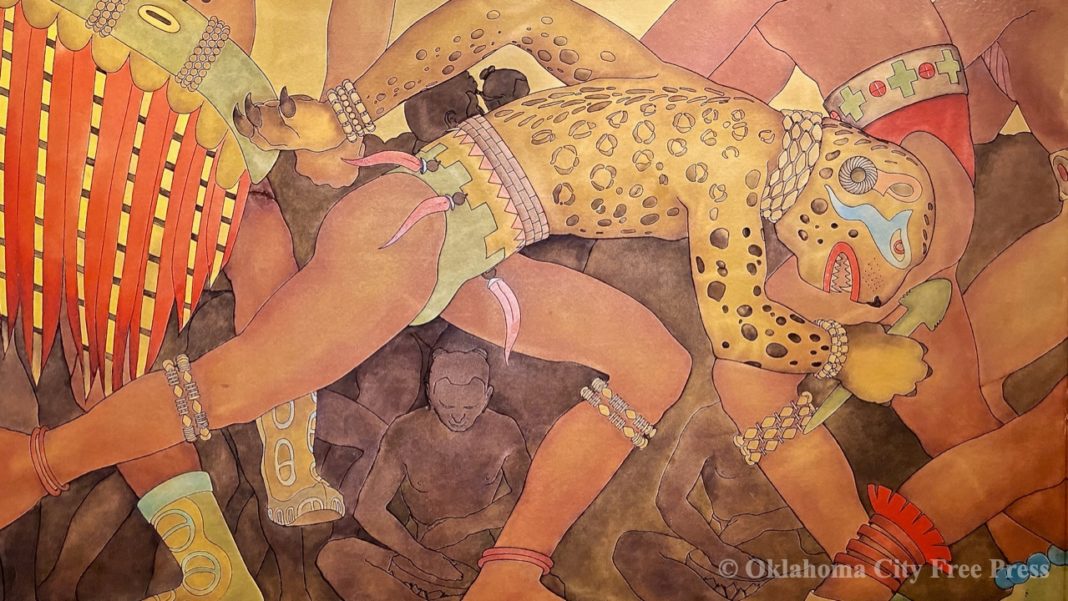

The Museum also included contemporary works by Native American artists. These pieces speak to the sense of continuity that connects the Wichita and Caddo people to their Spiro ancestors and informs viewers that the exhibition is a narrative that is not finished writing itself.

In particular, Mr. Spellman notes that it was crucial for the Museum to not strictly segment these contemporary pieces apart from the ancient artifacts, but instead intersperse them (for example, a beautiful rendering of ancient Native American dress), to “remind you that these were people!” and not just somber relics, “who lived in a land we are currently occupying as Oklahomans.”

The exhibition itself begins not with indigenous artifacts, but instead with pages from a German book detailing the lives of the Mississippian peoples in startlingly detailed imagination. These pages add a layer of insight into the exhibition. It is not just a history of the Spiro Mounds, but a history of the Spiro Mounds, confronting the contemporary viewer with evidence of his or her own predetermined conclusions.

As viewers proceed throughout the exhibition, they are therefore always conscious of the way colonialism has impacted the story now told afresh. This section of the exhibition provides a general overview of the Mississippian culture and its various settlements before visitors are confronted with the vast treasury of artifacts found at the Spiro Mounds.

Vast trove

Rounding the corner to the second part of the exhibition thus feels much like Howard Carter felt when he first set eyes on the fabulous tomb of King Tut. The sheer vastness of the collection, compounded by the knowledge that much more has been demolished or lost, is enough to stop visitors in their tracks.

Few Oklahomans would be aware that a trove of such ancient proportions and such scientific magnitude lies within our borders.

What is most exciting, however, is the stunningly complex level of work each piece possesses. As the museum labels on the walls will inform visitors, the pieces suggest similarly originated, but nonetheless distinct, styles of art. Some, in particular, are so distinct as to cause a double-take. According to Dr. Singleton, his team has “identified a piece of obsidian from the Valley of Mexico at Spiro and had it not been looted, likely would have found many other items.”

Though he is clear that “there is no evidence that there were significant connections” between the Aztecs and the Spiroans, there are suggestions nonetheless of trade links and ideological similarity.

The Spiroan artifacts, however, are entirely fascinating even without sensationalism of these purely hypothetical links. Each carved shell, each statuette pipe, and each wrought tool summons to viewers’ minds a vision of the person who must have created these pieces, centuries and eons ago, perhaps very close to where they are now viewing that creation; it is an awe-inspiring effect.

Response to climate change

The education children and adults alike can gain from this exhibition, however, is practical as well. The evidence suggests that the unique gathering of diverse artifacts at Spiro was a result of a very specific and intentional response to climate change in that era. Oklahomans can learn a great deal from the Spiro peoples’ united effort to discuss and deal with the effects of climate change, for, as Dr. Singleton notes, “if we do not try to prevent it, or react to it, quickly enough, large portions of our population will likely face extreme difficulty.”

McGirt v. Oklahoma

But the history of Oklahoma, though steeped in a great deal of tragedy, is optimistic on that front, as suggested by the Supreme Court itself. Though its decision in McGirt triggered a reckoning with our foundational and fraught history with Native Americans, there is much to learn from it, for as Justice Gorsuch wrote, “[w]ith the passage of time, Oklahoma and its Tribes have proven they can work successfully together as partners.”

Spiro Mounds indicates not only that such a spirit is still alive and well, but necessary for the preservation of the past and the continuity of the future.

The exhibit runs until May 9, 2021, at the National Museum of Cowboy and Western Heritage in Oklahoma City, before traveling the country at various institutions. Masks are required and tickets can be purchased at the front desk.

Devraat Awasthi is an art reporter for Free Press, a full-time law student at the University of Oklahoma, and is interested in pop culture’s role in public communities.