Last Updated on August 6, 2023, 9:31 PM | Published: February 21, 2023

Oklahoma’s “nonstop executions” traumatized corrections staff, leaving them vulnerable to mental health distress and botched procedures, nine former Department of Corrections officials warned last month.

“Reports from the Oklahoma State Penitentiary describe near-constant mock executions being conducted within earshot of prisoners’ cells, staff offices, and visiting rooms,” according to a letter to state Attorney General Gentner Drummond. “Correctional staff have communicated privately with visiting defense mental health experts about the distress they are experiencing due to the nonstop executions.”

Among those signing the letter (see below) were former DOC directors Joe M. Allbaugh and Justin Jones, and former state penitentiary warden Dan Reynolds. The letter, dated Jan. 13, asked Drummond to petition courts for a revised execution schedule “spacing them a minimum of several months apart to ensure the safety and well-being of the state’s correctional employees.”

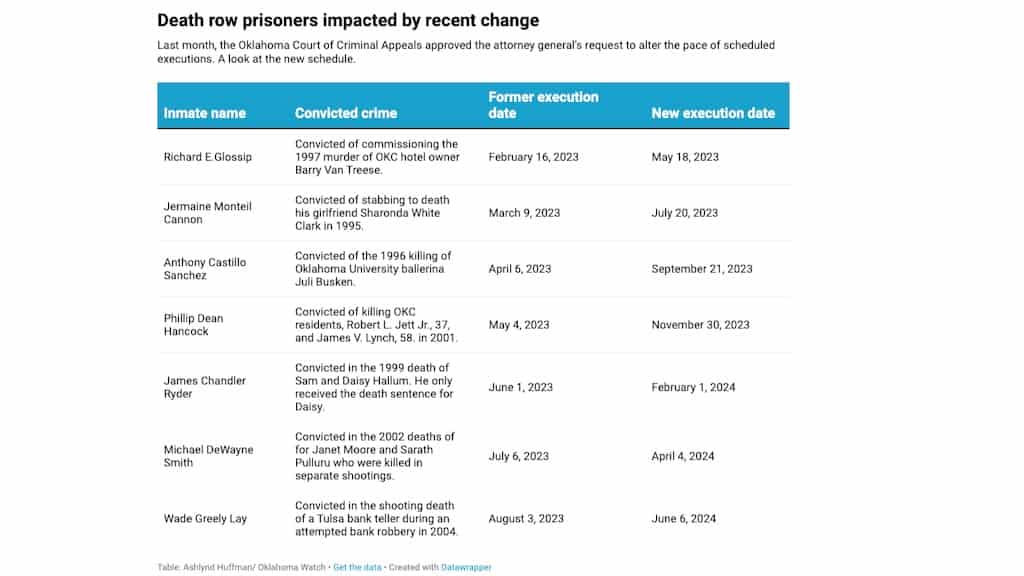

On Jan. 17, Drummond requested that seven impending executions each be delayed by 60 days. The state Court of Criminal Appeals consented, resetting the 25 executions in 29 months pace it approved in 2022.

“That relentless pace of executions means the prison never really returns to normal operations after the emotional and logistical upheaval of an execution,” the former DOC officials wrote in the letter, obtained by Oklahoma Watch through the state’s Open Records Act.

Drummond took office on Jan. 9 and was in McAlester three days later to meet with corrections staff and witness the execution of Scott James Eizember, who was convicted for the 2003 murders of A.J. Cantrell and Patsy Cantrell in Canadian County.

“I was there with them at 6:45 a.m. when they started their morning and stayed with them until they did their postmortem exit brief, with the mental health professionals there to provide services,” Drummond said in an interview with Oklahoma Watch.

Just as the penitentiary staff was concluding one execution, it began preparation for the execution of Richard Eugene Glossip, which had been scheduled for Thursday.

“As I was finishing my interviews with certain personnel, they said, ‘You know, Mr. Drummond, can we break? I need to grab a quick sandwich ’cause I start on Glossip at (1 p.m.),’” Drummond said. “And I thought, man, that’s unhealthy. And so I started asking more questions, and it’s just too onerous.”

Drummond said he filed the motion to delay and then space out executions only after talking with victims’ families.

“I’ve talked to every family that was affected. There was some frustration, but there was a lot of awareness of the demands on DOC. And so, in the end, every family member agreed. And we proceeded with that,” he said.

The letter from former corrections officials cited statistics showing an increased risk of suicide, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and substance abuse for those who carry out executions.

“There are significant costs with these kinds of compressed time period executions,” said Ngozi Ndulue, the deputy director of the Death Penalty Information Center, said in an interview last fall with Oklahoma Watch. “There are financial costs, but there are also emotional costs, which almost seems to downplay it a little bit.”

Oklahoma and Texas each carried out five executions in 2022, accounting for 56% of all executions nationally, according to the Death Penalty Information Center’s annual report.

The state resumed executions in October 2021 following a seven-year moratorium triggered by the botched executions of Clayton Lockett and Charles Warner.

In 2014, Lockett writhed and groaned during his execution when the state used the surgical sedative midazolam for the first time.

Warner’s execution, scheduled for the same night, was postponed for what the state said was a problem with an intravenous line. A medical examiner’s report showed the state used the wrong drug — potassium acetate instead of potassium chloride — in 2015 to stop Warner’s heart.

The letter to Drummond emphasized the potential harm of mistakes on those carrying out an execution.

“If even a routine execution can inflict lasting harm on corrections staff, the traumatic impact of a botched execution is exponentially worse,” the letter said. “Oklahoma has experienced this harm on multiple occasions and should not needlessly place its hardworking correctional staff at risk of another such mistake.”

letter-to-drummondPaul Monies contributed to this report.

Published in partnership with Oklahoma Watch under Creative Commons license. Free Press publishes this report as a collaborative effort to provide the best coverage of state issues that affect our readers.

Ashlynd Huffman is an investigative reporter for The Frontier. Contact her at [email protected] and 405-240-6359. Follow her at @AshlyndHuffman.