Last Updated on March 7, 2021, 10:46 PM | Published: February 6, 2020

OKLAHOMA CITY — The body of Tamara Lee Tigard was found on the edge of the North Canadian River near Jones with multiple gunshot wounds April 18, 1980.

It was her 21st birthday. But no one investigating that day had any idea.

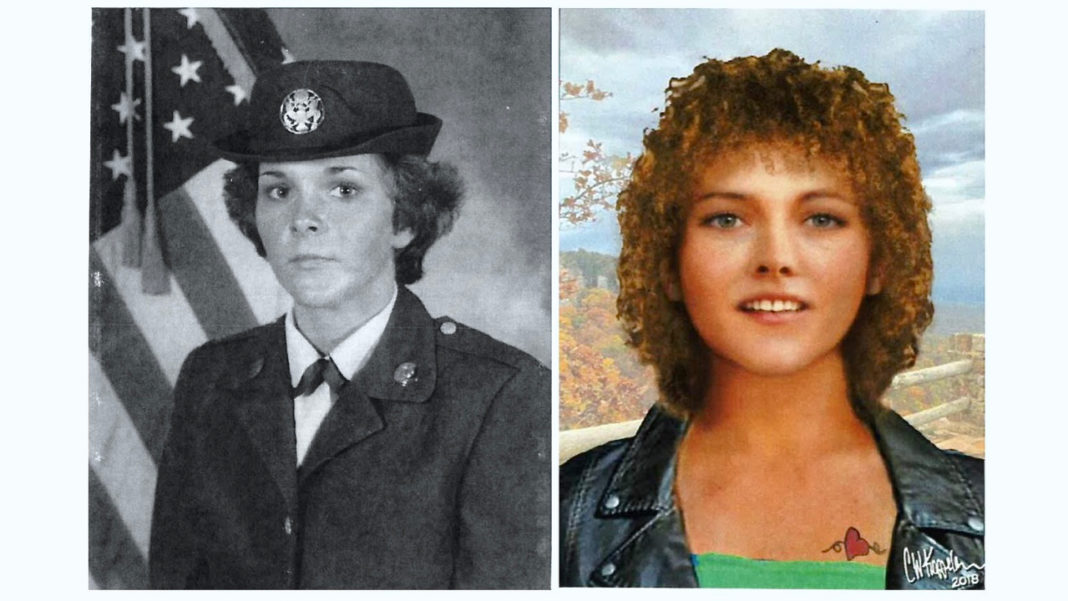

Authorities didn’t know whose body they had found back then or much of anything else about her. She was caucasian and had a small tattoo of a heart over her left breast.

All traditional methods of investigation failed.

She remained buried as “Jane Doe” in an undisclosed grave in Oklahoma City for the next 40 years.

During that time, her parents and siblings all died never knowing where she was or what happened since her disappearance from Las Vegas in 1980.

But, a volunteer organization using new DNA methods, a determined Oklahoma County Sheriff‘s (OSCO) investigator, the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation (OSBI) and Oklahoma Medical Examiner’s office all contributed to her successful identification in December.

The feature photo shows Tigard’s official U.S. Army photo (left) and an earlier artist’s reconstruction derived from her remains.

Persistence

Captain Bob Green over the OCSO Investigations Division told Free Press that he “inherited the case” from a previous investigator and just kept coming back to it to see if they had missed anything.

Several of the other people involved in solving Tigard’s identity praised Green for his persistence.

OSCO had been called to the crime scene in 1980 and the case was still an open one when Green got it.

“Lime Lady”

Tigard’s body had been covered in lime.

Investigators believe someone, perhaps her killer, mistakenly thought it would speed up decomposition. Instead, it helped preserve the body over the several days they estimated it had been there.

The unique mistake prompted crime writers across the nation to start calling her “Lime Lady.”

The national attention could have resulted in identification but it didn’t.

Instead, in 2019, the differences were advances in DNA sequencing and The DNA Doe Project, a volunteer organization formed by two physicians and staffed by many more volunteers, who worked with geneticists to connect the “Lime Lady” with her real name.

Green was the one who initially reached out and recruited the organization to help.

Preservation of evidence

After the press conference where Tigard’s identity was revealed, Free Press talked with Oklahoma Chief Medical Examiner Eric Pfeifer, M.D. and Angela Berg, anthropologist from that office.

“We have skeletal material that you can use which usually we can preserve pretty well there,” Berg told us. “But, once you go to blood, spleen, mouth swabs, those degrade pretty quickly especially if they’re not in the right environment.”

She said, “I’ve had cases where they were in storage sheds and yet have no profiles left because the heat the cold degraded them too much.”

“They didn’t know what they needed back then in 1980,” Berg said. So, it was a fortunate thing that the OSBI had turned over good samples to their office and that they had preserved the material well enough to still be sequenced.

It took some ingenuity at the ME’s office to keep samples preserved over the years, especially in their old building.

“We bought a gun safe and we put a heater dehumidifier in it so that it would make the right environment for it,” said Pfeifer. “And so when we moved into the new building, we built a room for it.”

DNA

With good samples that had been preserved by the ME’s office, possibilities turned into success.

Fuller, with the DNA Doe Project, said it took much longer to finally get a useable DNA profile in the first place.

One organization could not sequence her DNA but eventually, a second one did.

“On October 11, (2019) the sequence data was sent to our body informatics team where Dr. Gregory Magoon created a Jed match uploadable kit for her. And on October 30, her kit was uploaded to GEDmatch,” said Binder.

Once they got to that stage, it only took one day and one-half.

Binder said that with the limitations of the opt-in, only 17% of matches to Tigard’s DNA came up, yet she was identified quickly.

GEDmatch was in the news in 2018 when, with their assistance, police were able to identify the “Golden State Killer” who is suspected of committing 12 murders and raping over 50 women.

The company now has a policy of only allowing police to use their data in for certain types of crime and only the DNA of clients who specifically opt-in for law enforcement use.

Other references

There weren’t many unique aspects of Tigard’s young body except for a small tattoo of a heart above her left breast, and that did help as a cross-reference.

We asked Binder if, with the DNA and dental records, the tattoo even mattered in the end.

She said Green found a missing persons report with the Las Vegas Police Department that had been filed in 1980.

“It did mention a tattoo which made us more certain that we knew who we were looking for now,” said Binder. “The missing persons report also had the picture attached which matched our forensic reconstruction that was done. So, when you put it all together, it looks really good.”

Another important set of cross-references were the dental records from Tigard’s time in the U.S. Army.

Berg, with the ME’s office, told Free Press, “we got very lucky in this instance that those were still around. The dental records were actually X-rays that were taken in 1979 a year prior to her death.”

“Not over”

Captain Green said now that they know an identity “we go to phase two now … to see if we can figure out exactly what happened and who was involved.”

We asked Green during the news conference if he had any suspects in mind.

“I actually have a few people to talk to,” Green said. “It’s not over.”

Founder, publisher, and editor of Oklahoma City Free Press. Brett continues to contribute reports and photography to this site as he runs the business.